What will the financial impact of the Olympics be in Long Beach? Officials don’t know

The city has not conducted an independent economic impact study but maintains all costs should be offset and that worldwide exposure will be a boon for the city.

Early in the planning process for the 2028 Olympic and Paralympic Games in Los Angeles, the city of Santa Monica was tapped to host the beach volleyball event — a no-brainer considering the sport as we know it today was created on those same sands over a century ago.

Those preliminary talks began with LA’s first bid for the Games back in 2016. Actual negotiations began in 2023 and came to an end in early April after Santa Monica and LA28 (the local organizing committee for the Games) failed to “agree to terms around community benefits, operational details and financial guarantees,” according to the city.

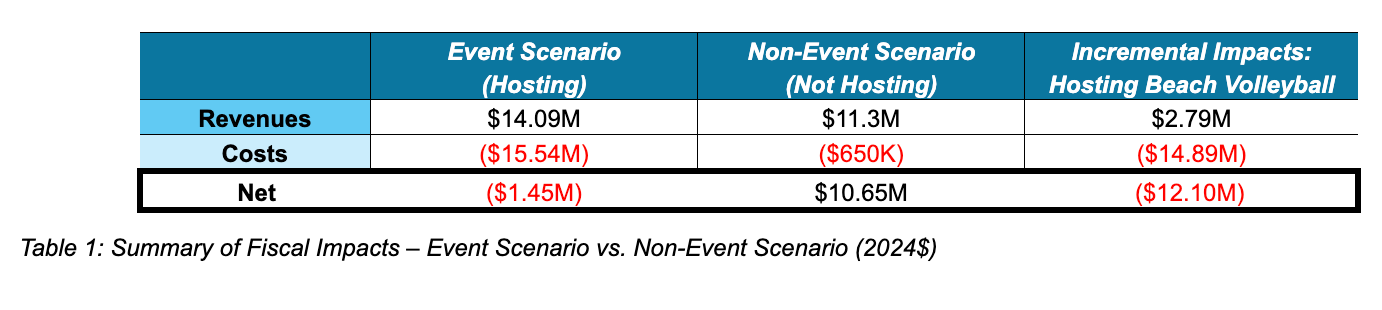

Among Santa Monica’s concerns were the projected financial impacts should it host the event. According to an economic impact report commissioned by the city council from HR&A Advisors, the city stood to lose an estimated $12.1 million if it hosted beach volleyball. In the report, HR&A projected a net loss of $1.45 million if Santa Monica were to host the event, compared to a net gain of $10.65 million should it not.

The report stated the city would still see increased visitation due to the Olympics being in the region without incurring the operational costs.

Less than two weeks after negotiations between Santa Monica and LA28 fell apart, it was announced Long Beach would host beach volleyball at Alamitos Beach.

The city of Long Beach, however, which is slated to host more events (18) outside of LA proper than any other city, has not conducted an independent economic impact report, which would look at estimated costs such as public safety and refuse collection as well as revenue generation.

Instead, the city is awaiting an economic impact report from LA28, which is expected to be released “in the coming months,” LA28 officials said in an email last week. The report will include projections related to Long Beach, according to officials, but it’s unclear how detailed individual city impacts will be reported.

“Given that the 2028 Games are a regional effort involving multiple host and venue cities, the City’s approach has been to first review the broader analysis already underway before determining whether any additional evaluation specific to Long Beach would be necessary,” city spokesperson Kevin Lee said in a July 3 email.

In the 129 years since the modern Olympics began, only two cities have turned a profit as host: Paris last year, which netted just shy of €27 million, per Visionary Marketing; and LA in 1984, when it finished with a $215 million operating surplus, according to the Council on Foreign Relations.

“Los Angeles was the only city to bid for the 1984 Summer Olympics, allowing it to negotiate exceptionally favorable terms with the IOC,” the CFR wrote last year, also noting that LA utilized existing venues, not unlike its 2028 plan. “A growing number of economists argue that the benefits of hosting the games are at best exaggerated and at worst nonexistent, leaving many host countries with large debts and maintenance liabilities.”

But Long Beach officials remain confident that the Games won’t put the city in the hole.

“The intent certainly is to go into it … for the full cost offset,” City Manager Tom Modica said in a May interview with the Watchdog. Santa Monica, he noted, is a small city and the volleyball event would have disrupted its greatest revenue generator: the beach and pier.

“We’re Long Beach, hence the name, so we have lots of space to spread these costs over 11 venues,” he continued, adding that if LA28 had selected an area outside those already tapped for other events, it would have been “really hard to say ‘yes’” to taking on beach volleyball.

Modica explained that one of the major expenses in past Olympics was the construction of venues, many of which now sit abandoned and crumbling around the world. LA28, however, has no plans to build permanent facilities, but rather use existing or temporary ones — and host cities are not on the hook for construction costs, which is noted in the city’s “Strategic Roadmap” for the Games.

The roadmap outlines 75 revenue and cost “segments,” breaking down which city department is impacted and who is responsible for funding. Of those identified segments, only four are expected to generate revenue: increased traffic at Long Beach Airport; increased fines from bylaw enforcement; increased towing fines and impound fees; and increased ambulance transport and first responder fees.

Television rights, ticket sales, and sponsorships make up the vast majority of revenue for the Games, but the International Olympic Committee keeps a large portion of that revenue, according to the CFR.

And, of course, there will be tax revenue from visitors staying in local hotels, eating at local restaurants and shopping in the city, Modica noted.

The remaining 71 segments are expenditures, which are labeled according to who is likely to be responsible for covering the costs — some of which are non-discretionary (meaning they are fixed and cannot be avoided), while others are controllable. Of those cost segments, 10 are expected to be paid for by LA28 alone.

Costs for seven segments — five of which are non-discretionary — are expected to be shared between the city and LA28, according to the roadmap. Those shared between LA28 and the city include lifeguards/marine safety/water emergencies; water garbage cleanup; law enforcement/crowd control; garbage pickup and recycling; designated Olympic traffic lanes; power hookups by generator; and water and sewer maintenance.

Another four non-discretionary costs are expected to be borne by the city alone: general public health; traffic management; traffic signal maintenance and timing; and lost revenue from parking meters and parking enforcement.

The city’s largest ongoing expenditure is Elevate 28 — the five-year, billion dollar infrastructure plan consisting of hundreds of projects to improve the city’s mobility, parks and public facilities. Funding for these projects comes from the city’s Measure A sales tax as well as a host of other sources such as LA Metro, the state gas tax, various grants and more. These are general improvements that residents will continue to enjoy for years to come, according to Modica.

“Those are things that we likely would have done with or without the Olympics,” he said.

The remaining 41 identified roadmap cost segments, which are deemed “controllable,” are expected to be covered by the city. These costs are varied and include beautification, planning and coordination across numerous city departments, time management across departments, fleet operations, safety services for city employees and more.

Some additional city staff has already been hired to prepare for the Olympics, Modica said, and more positions could be added ahead of the Games. A Program Management Office to “serve as coordination point for alignment, tracking, communications and risk management across the various projects needed for success Games hosting” could also be established, according to the roadmap.

“Our expectation is that as we move forward, we will be negotiating cost neutral and basically cost recovery for the supplemental services,” Modica said of ongoing talks with LA28.

As for ongoing issues like homelessness and crumbling streets, Modica says it’s “unrealistic” to expect those to be solved with the coming of the Olympics, but said the city is committed to continuing work on the problems most important to residents.

“In order to do that, you’ve got to be able to maintain a good economy,” Modica said. “This is part of it. We get a lot of funding from visitors coming in and spending their dollars here.”

In many host cities, including Long Beach, existing facilities are slated for use. The Long Beach Convention Center and Arena are set to host four events. Those facilities are strong revenue generators via conventions and other events, which will not be able to take place during the Games as well as the weeks or months leading up to them.

“We've signed agreements basically saying that they can use certain venues and we agree to make those available,” Modica said. “In those high-level documents, it basically sets the city's expectation that that is going to be cost recovery — if they take the convention center, and it would normally make a rental rate for several months of a certain amount, then they owe that certain amount to make it flat.”

Modica pointed to the city’s long history as host to the successful Acura Grand Prix of Long Beach as proof that the Games can run smoothly without being a drain on city finances and resources. During the three-day race event, Modica said there are essentially two cities operating: the race venue area and the rest of the city.

City police and fire department personnel as well as Public Works and other city staff are working within the race venue in addition to normal operations citywide. Those dedicated to the event are funded by the Grand Prix Association of Long Beach, Modica said.

Modica said that the Olympics will, depending on negotiations with LA28, operate on a similar model. The scale between the grand prix, which exists in one confined location, and the Games, which will take over numerous areas along the city’s 11-mile waterfront — from the Convention Center to Marine Stadium — is not exactly a one-to-one comparison.

The olympics are set to take over the following areas: Alamitos Beach (beach volleyball, blind football (soccer)), Long Beach Arena (handball, sitting volleyball), Belmont Shore (sailing, coastal rowing, open water swimming), Convention Center (shooting, shooting para sport), Convention Center Lot (artistic swimming, para climbing, para swimming, sport climbing, water polo) and Marine Stadium (canoe sprint, para canoe, para rowing, rowing).

While there may be one or two “fan zones” funded and operated by LA28, Modica said the city is also looking into its own viewing areas in parts of the city far removed from the fanfare, such as North Long Beach, to allow residents to “participate without having to come into Downtown, but still have the Olympic spirit.”

“Obviously, security is going to be much different there than at the Olympics, and so those are going to be very low-cost items,” Modica said, adding that funding will be identified in upcoming budget cycles.

Modica noted that the city has a dedicated fund to pay for events. Separate from the General Fund, the Special Advertising and Promotions is funded through the city’s hotel bed tax. In addition to events like parades, the fund also pays for arts programs, according to Modica.

“We have been looking at building that reserve over the next several years,” Modica said. “It’s doing healthy now, as we’re back from the pandemic. We’re actually bringing in more revenue than we did at the height of 2019.”

But money isn’t everything when it comes to hosting the Games, according to Modica, as is the case with the Grand Prix race weekend.

“A big part of it is being seen all over the world,” he said. “The Olympics has that potential at a much higher magnitude. This is our moment to really show the world what Long Beach is all about.”

The Olympics coming to town has already had an impact on the city, Modica said, with individuals and businesses looking to move to Long Beach. The Games are a moment for the city to shed the “best kept secret” descriptor, he added.

According to the CFR, however, impact studies conducted by cities prior to the Games often argue that hosting the event will result in a “major economic lift” through job creation, tourism and increased economic output.

“However, research carried out after the games shows that these purported benefits are dubious,” the CFR said.

While some host cities saw boosts in tourism following the Games, others saw declines, the CFR noted. Similarly, a study of the 2002 Salt Lake City Games showed a short-term influx of jobs but no long-term employment gains.

“Ultimately, there is little evidence for an overall positive economic impact,” the CFR wrote.

The CFR commentary is based on normal circumstances for host nations. The 2028 Games, however, have a variable that no prior Olympics has: President Donald Trump.

The Trump administration’s immigration crackdown, which has seen even legal residents and American citizens hauled off by masked agents in unmarked cars, as well as recent travel bans could have an adverse effect on the Games. As LA Times Business Columnist Michael Hiltzik notes, all 12 countries on Trump’s travel ban list, as well as 36 others that could be added, sent athletes to the 2024 Paris Games — not to mention officials and fans.

While the policy does make an exception for athletes, coaches and immediate relatives, it mentions no such exception for fans, according to the Associated Press. LA28 Chair Casey Wasserman, however, is on record saying the White House understands the need to be “accommodating” when it comes to visas for those coming to the Games. But concerns persist, Hiltzik writes.

“Are those assurances reliable? Trump’s policymaking record is inauspicious,” Hiltzik said. “Whether the product of deliberate policymaking or whim, Trump’s capacity for sabotaging the … Olympics is vast.”

Already this year, numerous countries have issued travel warnings and advisories for people thinking about visiting the U.S. as the stricter border enforcement has already led to the detention of Canadian and European tourists, the BBC reports.

"The combination of travel bans and a reduction of U.S. travel could have a material impact on tourism and economic development," Jeff Le, former deputy cabinet secretary for the State of California and the state's federal coordinator during the first Trump administration, told the BBC.

Hiltzik pointed to ticket sales for the FIFA Club World Cup, which wrapped up Sunday at MetLife Stadium in New Jersey, noting that organizers slashed ticket prices to matches by as much as 77%. An analysis by The Athletic found that the soccer matches averaged crowds of less than 35,000, with some matches being viewed by thousands of empty seats.

While there is no way to make a direct connection between current U.S. immigration policy and the overall underperformance of FIFA ticket sales, Hiltzik did not rule it out. Additionally, he noted that Trump is unpredictable and in recent months has voiced his contempt for LA — and California as a whole.

But Modica and other city officials are undaunted and determined to make sure the Olympics can only be a positive for Long Beach.

“This is an exciting opportunity. We know everyone is going to be watching this,” Modica said. “We’re taking this very seriously. A lot of thought is getting put into how to make this fiscally sustainable, how to make sure we're aware of impacts on the city and its residents, but also really being able to put our best foot forward and put Long Beach on the national stage.”

We need your support.

Subcribe to the Watchdog today.

The Long Beach Watchdog is owned by journalists, and paid for by readers like you. If independent, local reporting like the story you just read is important to you, support our work by becoming a subscriber.