‘This is rock star stuff’: From Long Beach metalhead to playing taiko for millions

Drummer Kaz Mogi, a Long Beach native, took the stage with a massive Japanese drum during the 10th annual Game Awards as part of an emotional announcement.

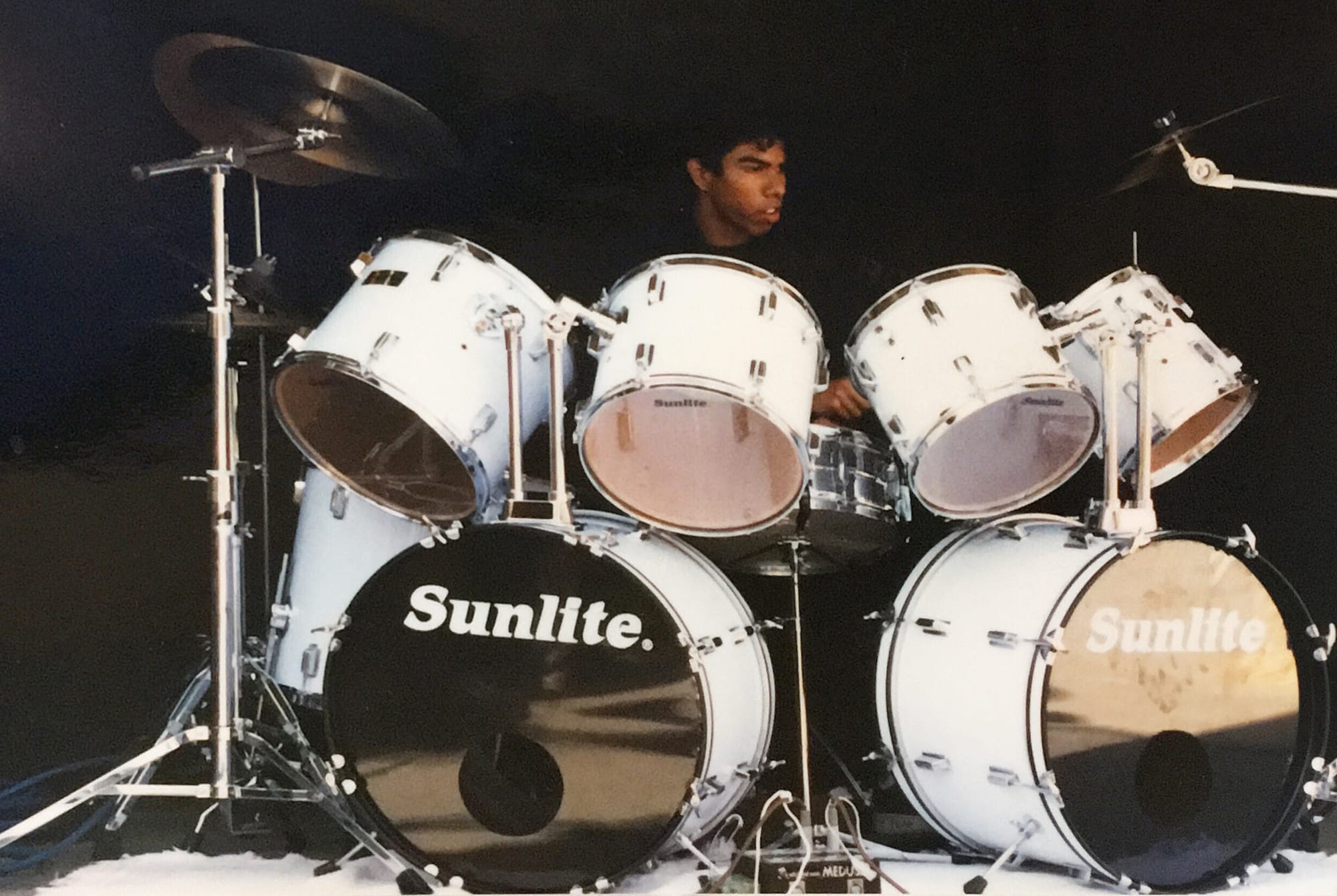

During the summer between sixth and seventh grade, Kaz Mogi became obsessed with drums after watching Metallica’s “Sad But True” music video. He had just started getting into metal as a genre, but the video ignited a lifelong passion.

“It was a live video of them playing to tens of thousands of people and I saw Lars' drum set and thought it was really cool,” Mogi said. “That’s what really got me to want to start playing drums.”

His dad bought him a drum set and he spent his summer inside, eight hours a day, teaching himself to play.

“I was obsessed,” he said.

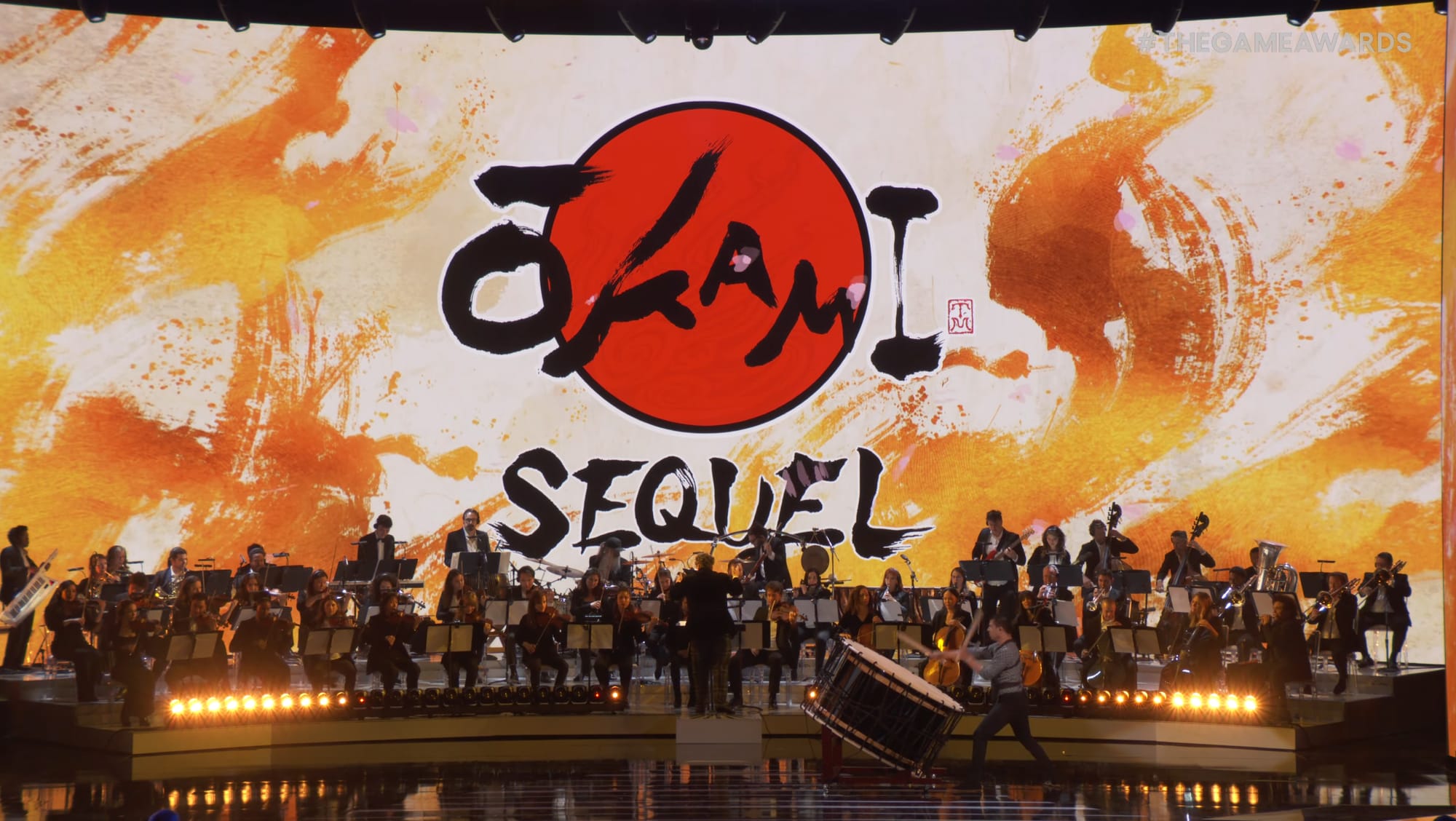

Three decades later, Mogi, now 42, found himself center stage with a massive Japanese drum called a taiko, in front of thousands of live audience members as well as over one million streamers during the 10th annual Game Awards, which recognizes video games and their developers each year.

As of Saturday afternoon, the YouTube Live video from the event racked up more than 10.7 million views. Though final figures have not been released for Thursday night’s ceremony, in 2023 the awards show had 118 million total viewers, according to Forbes.

“I’m not a gamer, I didn’t really know about the Game Awards,” said Mogi, whose taiko playing can be heard on Sony Playstation's “The Ghost of Tsushima” and “Avatar: The Last Airbender” on Netflix. About 20 minutes before he was set to perform, Mogi said he found the YouTube Live link and texted it to his dad.

“I saw a million people were watching and was like, ‘Oh shit, this is a big deal,’” he said.

Reaching this milestone was a long road for Mogi, who was born at Long Beach Memorial in 1982 to a Japanese immigrant father and a first-generation Mexican mother. The family lived in Lakewood on the border of Long Beach until Mogi was in ninth grade and they moved into Long Beach.

When he first picked up the drums, he was attending Bancroft Middle School.

After the summer of teaching himself, Mogi decided to join the school band. But his teacher did not allow beginners to play drums, he recalled. So he played the flute — for two days.

“She heard me playing on a drum and she’s like, ‘OK, you can play drums for band,” Mogi said, adding that he went on to also play for the school’s jazz band and orchestra.

Mogi attended Lakewood High, where he continued honing his percussion skills. He played in the school band all four years, including being section leader on drumline the last three years and assistant drum major the last two years. He started on the bass drum, then moved on to the snare and finally the quad drums.

After graduating in 2000, Mogi enrolled at Long Beach City College. Because the path to an associate’s degree in music was long and he wanted to graduate as soon as possible, he instead got a liberal arts degree. But he also played drums with the school’s show band.

While at LBCC, Mogi returned to his alma mater as Lakewood’s drum coach in 2001, a position he held for more than a decade until he left in 2013.

Looking to focus on music after community college, Mogi attended Musicians Institute, a private music-focused school in Los Angeles, where he studied drum set for a year.

“That was amazing,” he said. “I grew so much in the year that I was there and drum set was always what felt like home.”

At the insistence of his parents, who said he needed a backup plan, Mogi then enrolled at Cal State Long Beach, where he received a degree in music education. He said he did not enjoy the program because he already had years of teaching under his belt as drum coach at Lakewood.

“The stuff they were teaching, I was like, ‘Yeah, that’s not gonna work for high school kids,” Mogi said with a laugh. “But I made it through.”

A few years after graduating, Mogi decided he wanted to reconnect with his Japanese heritage. First, he joined an aikido club at CSULB, where he studied the modern Japanese martial art form. But it wasn’t for him.

He had a friend who played taiko and decided to give the instrument a try.

“I only had the intention of taking classes for fun, but one thing led to another and I joined a performing group and started doing gigs,” Mogi said.

Free gigs turned into paying gigs turned into connections within a broader industry.

Those connections paid off when Mogi got a call to play on the critically acclaimed game “Ghost of Tsushima,” which was released for the Playstation 4 in July 2020. The game garnered 47 award nominations and a dozen wins, including Outstanding Achievement in Original Music Composition at the 24th annual D.I.C.E Awards.

He was brought back into the studio for the “Ghost of Tsushima” downloadable content, or DLC, which led to another job playing on Netflix’s “Avatar: The Last Airbender,” he said.

“Once you’re in that circle, word starts spreading if you do good work,” Mogi said. “I’m sure that’s how I got the Game Awards — a friend of mine knew I had experience playing with an orchestra.”

Of course, not all of his taiko gigs are top-tier studio and live performances, he said. Some recent freelance jobs include a 50th wedding anniversary, educational school and library sets and company holiday parties. For these jobs, Mogi is part of a network of taiko players who share work because they usually require multiple drummers.

The big jobs are few and far between — about one per year, he said, adding that he is currently working on another game under a non-disclosure agreement, and hoping to get a call back for “Avatar: The Last Airbender,” which Netflix renewed for two more seasons.

“The stress you get from a job you hate and the stress that I get from not having consistent income are different,” Mogi said of quitting his desk job in 2022 to focus on music. “It’s stressful but it’s not a soul killer.”

While many of his freelance and studio gigs see him fading into the background as party goers talk over the music or as background percussion in a more elaborate composition, the Game Awards performance highlighted Mogi. Literally. He and his 48-inch drum — the largest he’s ever played — were positioned at the front of the stage with a spotlight and camera trained on his every move.

“It’s really nice to do something like that every once in a while, when on the flip side, doing gigs like playing for a restaurant, people don’t give a shit — or they’re annoyed because they’re just trying to have dinner and you’re playing loud taiko in front of them,” Mogi said laughing.

But the event came with some stress beyond having over a million eyes on him, Mogi said. Originally, he was supposed to have sheet music on stage to read from during the performance. The day before the awards show, however, he was asked if he could memorize it, which he did.

The drum he played during the event was also more than twice as big as the 20-inch drum he normally plays and requires much larger sticks.

But he adapted and the performance went off without a hitch — almost. Mogi did admit to flubbing one part. The mistake, though, was minor and only musicians with a keen ear would be likely to notice, he said.

And the moment was huge. The musical performance was part of the final reveal of the night: a trailer for a sequel to “Ōkami,” a beloved Capcom title released for the PlayStation 2 in 2006. Ahead of the trailer, which played in sync with the orchestra, Game Awards founder and host Geoff Keighley was visibly emotional.

Despite the challenges and stress of the moment, Mogi said the Game Awards was unlike anything he has ever experienced.

“I was able to mingle with the orchestra backstage, but going on stage, I had my own escort,” Mogi said. “The orchestra went out at a different time and I’m just standing there with my own escort like, ‘Damn, this is rock star stuff.’”

“It was great. It fulfilled a childhood dream of playing for thousands of people — millions of eyeballs, apparently,” Mogi said. “It’s definitely something I’ll remember forever.”

We need your support.

Subcribe to the Watchdog today.

The Long Beach Watchdog is owned by journalists, and paid for by readers like you. If independent, local reporting like the story you just read is important to you, support our work by becoming a subscriber.