Community rallies to save ‘rare gem’ in Lakewood Equestrian Center as city officials weigh closure

Lakewood officials did not inform the five women-owned businesses or the dozens of people with boarded horses that the facility could be shut down, one horse owner said.

Under a tree on a hot summer morning, 7-year-old Lou Brouttier sits next to her mom Blake, waiting her turn as she watches her younger sister during her horseback riding lesson.

Lou and her 5-year-old sister Vada have been taking Western riding lessons at the 19-acre Lakewood Equestrian Center for about a year, Blake said, making them the third generation of riders in the family.

“With the hustle and bustle of the city, it’s very convenient to have a place where everything’s calm, very mellow, for them to learn about responsibility and be with the animals,” Blake said. “For them to have this opportunity so close to our house, it’s unique and definitely an experience they’ll remember for the rest of their lives.”

But this unique experience could come to an abrupt end as the city of Lakewood, which owns the property, considers the future of the facility, which has posted financial losses over the past eight months.

During its June 25 meeting, the City Council listened as staff presented it with two options: Increase the budget and continue the equestrian activities or reimagine the property with different amenities “for the greater public benefit.”

“[The center] means everything to us,” Paul Day, who has several horses boarded at the facility, said in a July 3 interview. “Our horses depend on us every day to take care of them and to nurture them and to be with them. The thought of putting them through all the stress of a move is just overwhelming to us.

“How would you feel having to drive 40 or 50 miles to see your dog or child?” Day added. He said city officials “need to stop thinking about the almighty dollar and pay a little more attention to the almighty horse.”

After listening to 54 people decry the loss of the equestrian center for hours, the council directed staff to take 60 days to draft a new option to continue equestrian operations with a smaller footprint as well as prepare a request for proposal for a new long-term operator.

But the council’s direction does not guarantee the longevity of the equestrian center, so the community continues to rally. Since June 26, a GoFundMe has raised nearly $15,000 of its $20,000 goal to help save the facility. Similarly, a Change.org petition to keep the facility has amassed more than 5,125 signatures since June 25.

“The way the community has rallied around the preservation of the Lakewood Equestrian Center has been deeply moving,” GoFundMe campaign organizer Alexa Rodell wrote in a June 30 update.

The city takes over

Horses have been boarded on the property at 11369 E. Carson St. since the early 1950s when the Glenn Spiller Stables opened. The city of Lakewood purchased the property in 1980 but has leased it to several operators since then.

Today, in addition to stables and riding lessons, the site hosts a petting zoo, pony rides and Wisdom of the Herd, a psychotherapy program that uses the animals to treat people with autism or mental health issues such as post-traumatic stress disorder. The space is also used for summer camps, parties and field trips.

The most recent operator retired in 2019, and city officials have so far not found a permanent replacement. In November 2020, the city contracted with SJ Equestrian, which has served as interim caretaker for three years, paying the city 8% of its gross receipts.

But the contract was not extended, and the city assumed complete management of the property late last year. Since the city began managing the center, it has found itself consistently in the red, forecasting a $110,000 net loss in fiscal year 2024 and projecting more than $2.5 million in losses over the next two fiscal years, according to a city staff report.

“For years it functioned in the black and now, in eight months, it’s to the point of closing,” said Michele Bloomquist, who runs a Western riding and horse training business at the center with her daughter, Hayley.

Lakewood city officials declined to answer questions from the Watchdog or provide details on the center’s profitability over the past several decades, stating “staff doesn’t have the time at present for an interview.”

The Bloomquists, whose history at the center dates back to 1966, said there was a “hard learning curve” for the city when it took over the facility, which the staff report also notes.

“They decided there was a lot of work that they wanted to do that was really important to them but not so much to the equestrian community here,” Hayley said, noting landscaping and tree trimming were early focuses of city management. “There were a lot of trucks coming and going and city staff didn’t know what scares horses.”

The center has stalls for up to 190 horses, according to the staff report. As of June, 112 stalls were occupied, down from 132 in October. The number of horses in dry lots also has decreased from eight to four over the same period.

Michele said most of the decline was from fear of having the city manage the facility without any of the necessary experience.

That inexperience has led to some expenditures that the Bloomquists can’t seem to figure out. For example, they said the amount the city pays for feed and hay is going up despite there being fewer animals on site and decreasing prices. In fact, feed prices fell almost 1% last year, according to industry research company IBISWorld, while ProAg notes hay prices have declined three years in a row.

Hayley acknowledged that the cost of the city doing business is inherently more expensive than a private operator in some ways, namely due to higher wages and sourcing restrictions that require a bidding process.

In addition to monthly losses, the staff report notes the city has identified over $6.2 million in improvements, including more than $1.8 million in recurring projects such as painting, reroofing and plumbing over the next decade.

The majority of the improvements expenses — nearly $4.4 million — are one-time projects for “addressing critical deficiencies, adapting to new regulations and enhancing the overall functionality” of the center. These include a stormwater management system, additional lighting and an electrical grounding system.

An assessment of the facility’s nine arenas found that seven are in “poor” condition and two are in “good” condition, but all require maintenance. In all, $434,624 is needed for restoration, drainage systems and other repairs, according to city staff.

Horse, business owners blindsided by possible closure

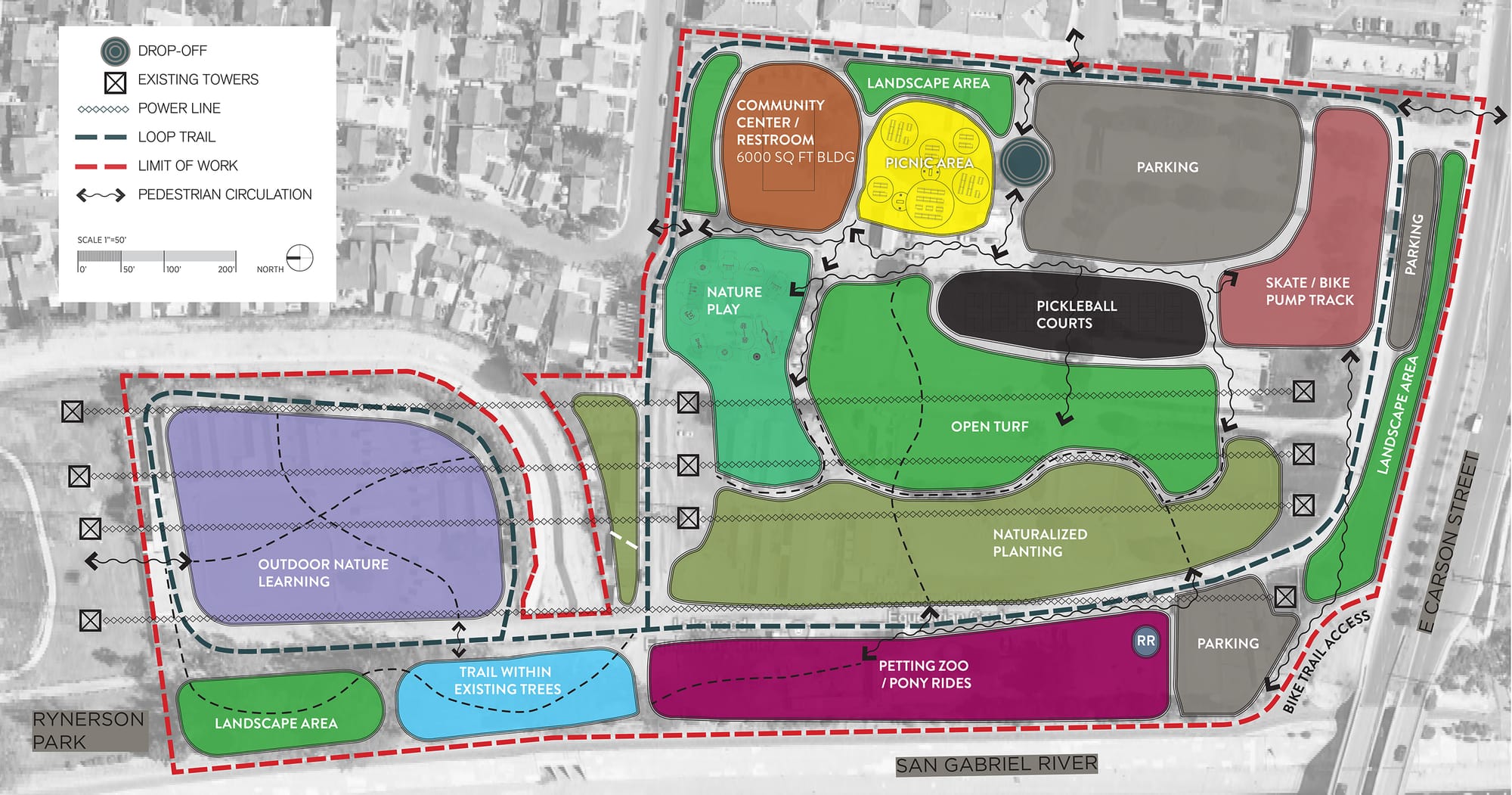

In response to the losses and looming expenses, city staff prepared a report for the City Council to consider during its June 25 meeting, which included the option of razing the equestrian center to make way for a “wider variety of uses.” The preliminary site map shows a skateboard pump track, pickleball courts, nature-themed play areas, a community building and walking paths that connect to Lakewood’s Nature Trail, Rynerson Park and the San Gabriel River bike path.

Regardless of the future use, the petting zoo and pony rides are expected to remain, according to the city.

The staff report did not include projected costs for the full redevelopment of the property. In Long Beach, however, playgrounds have cost the city anywhere from a few hundred thousand dollars to well over a million, and turf fields have run more than $2 million, according to reports.

The recent renovation of Long Beach’s El Dorado duck pond cost more than $11.4 million, according to city staff.

With a population of nearly 82,500 people and an area of less than 10 square miles, Lakewood has more than 100 acres of park space across nine parks, which include several pools and other amenities.

None of the five women-owned businesses nor the dozens of horse owners with animals at the center, however, were informed of the potential closure directly, according to Taylor Cohen, a boarder at the center. In a June 20 email sent to the “LEC Community” obtained by the Watchdog, Recreation and Community Services Director Valarie Frost told stakeholders she would give an update on the city’s management, including financials, statistics, capital improvement projects and funding needs.

“It didn’t say anything about shutting down whatsoever,” Cohen said. “We only found out because we looked at the meeting agenda.”

By law, public meeting agendas must be posted at least 72 hours prior to meetings. Lakewood City Council meeting agendas are typically published online “fairly close to the deadline,” according to city spokesperson Bill Grady. The June 25 agenda was posted the day after Frost’s email, giving the equestrian community just three days to rally supporters.

What happens next?

With the council opting to delay its decision, city staff has another 46 days to draft a potential site plan for a smaller facility. The new footprint would not include equestrian operations on land owned by Southern California Edison, which is leased by the city.

According to a statement on the city’s website, Edison’s “rigid” five-year land licensing makes it challenging for long-term planning and operations of horse stables, which “makes any capital improvements on that portion of land very risky.”

The city is slated to pay Edison $44,000 this year for the license to use the land. But the annual fee would be “dramatically” reduced to $17,800, according to staff, with the proposed passive uses rather than the equestrian business.

The city says that it is still open to a “qualified” person or organization taking over operations of the facility.

Cohen said the equestrian community has submitted two different proposals to the city for consideration but added that, so far, “the city has been crickets.”

“It’s such a rare gem to have something like this in the middle of an urban area,” Hayley Bloomquist said. “Once [the center] is gone, they’re never going to make more boarding facilities. They’re never going to make more experiences where you can be with nature and with animals in this kind of capacity.”

We need your support.

Subcribe to the Watchdog today.

The Long Beach Watchdog is owned by journalists, and paid for by readers like you. If independent, local reporting like the story you just read is important to you, support our work by becoming a subscriber.